Reconstituting Florentine Archives Online

Italian archives have not had it easy over the last 600 or so years. Those that managed to survive into the 20th Century despite the frequent wars and other calamities that effected the peninsula were subject to the ravages of the Second World War (many library and archives were severely damaged or lost in Allied and German bombing; for a rather harrowing evaluation of lost libraries and archives of the 20th Century see the UNESCO report Lost Memory, part of the Memory of the World programme). The trials for the archives of Florence that survived to the mid-20th century, however, the were not over.

On November 4, 1966, the Arno River flooded, unleashing upwards of six metres of muddy water into the streets of the city. The art galleries, libraries, churches and archives of the city were all affected, with many objects submerged in the sludge and heavily damaged. This includes the archives of the Cathedral (the Cathedral Square seen above, image from the exhibit Thirty Years After the Flood), which saw upwards of 6000 volumes dating back to the 13th century covered in mud and many were rendered illegible. However, an international effort was undertaken and a great deal was salvaged thanks to the efforts of the "Mud Angels" (see the exhibit image galleries for some remarkable photos). Apparently stuff is still in freezers waiting for conservation treatment almost 40 years on. Using new scanning technologies some of these once unreadable documents are now being made visible again. The Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, the administrative body that is responsible for the Cathedral, with a Getty grant and the assistance of the Max-Planck-Institut in Berlin and the University of Cologne, has undertaken the mammoth Years of the Cupola Project which, since 1994, have been painstakingly scanning, transcribing and analyzing the 20000 documents that cover the years of the construction of the Cathedral’s dome, 1417-1436. So far about 6000 documents are indexed and available in both Italian and English and they have just begun putting up digital facsimiles of the originals. Essentially, they are reconstituting the archive digitally. This project is not only making the archival materials accessible to a geographically dispersed audience, which is not terribly new or revolutionary but still a great thing to do, but they are also making documents usable that have not been able to be read for 40 years. This archival material will be of immense interest to historians of art, architecture, science and material culture, as well as ecclesiastical historians and others. As for me, I think it is supercool and I hope to see the techniques and lessons applied to other archival collections that have suffered damage (thinking perhaps of some of the stuff in Mississippi and Louisiana after the recent flooding or affected by last year's tsunami or countless other documents that have been subject to extreme water damage).

On November 4, 1966, the Arno River flooded, unleashing upwards of six metres of muddy water into the streets of the city. The art galleries, libraries, churches and archives of the city were all affected, with many objects submerged in the sludge and heavily damaged. This includes the archives of the Cathedral (the Cathedral Square seen above, image from the exhibit Thirty Years After the Flood), which saw upwards of 6000 volumes dating back to the 13th century covered in mud and many were rendered illegible. However, an international effort was undertaken and a great deal was salvaged thanks to the efforts of the "Mud Angels" (see the exhibit image galleries for some remarkable photos). Apparently stuff is still in freezers waiting for conservation treatment almost 40 years on. Using new scanning technologies some of these once unreadable documents are now being made visible again. The Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, the administrative body that is responsible for the Cathedral, with a Getty grant and the assistance of the Max-Planck-Institut in Berlin and the University of Cologne, has undertaken the mammoth Years of the Cupola Project which, since 1994, have been painstakingly scanning, transcribing and analyzing the 20000 documents that cover the years of the construction of the Cathedral’s dome, 1417-1436. So far about 6000 documents are indexed and available in both Italian and English and they have just begun putting up digital facsimiles of the originals. Essentially, they are reconstituting the archive digitally. This project is not only making the archival materials accessible to a geographically dispersed audience, which is not terribly new or revolutionary but still a great thing to do, but they are also making documents usable that have not been able to be read for 40 years. This archival material will be of immense interest to historians of art, architecture, science and material culture, as well as ecclesiastical historians and others. As for me, I think it is supercool and I hope to see the techniques and lessons applied to other archival collections that have suffered damage (thinking perhaps of some of the stuff in Mississippi and Louisiana after the recent flooding or affected by last year's tsunami or countless other documents that have been subject to extreme water damage).Here is a natural light image of a page (a detail, see here for the full page)

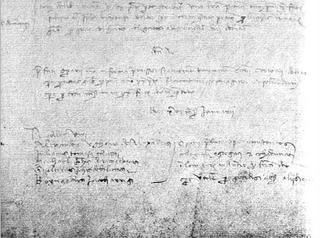

And here it is under low-intensity lighting:

rgsc